The Visualization Framework: Turning Mental Imagery Into a Practical Tool for Growth

I learned visualization's true power while working with Sarah, a grad student paralyzed by overthinking. A simple printed framework became her reset button—transforming endless analysis into purposeful action. Here's the systematic approach that changes everything.

A structured approach to using visualization for learning, decision-making, and intentional change

The highest-performing students, leaders, and innovators don't just think differently—they visualize strategically.

Research by cognitive psychologist Alan Paivio shows that people who combine mental imagery with systematic visual tools outperform those using either approach alone by significant margins. Yet most people treat visualization as occasional positive thinking rather than the precision instrument it can become for navigating uncertainty, accelerating learning, and designing intentional change.

The breakthrough isn't in visualizing more—it's in visualizing with purpose, using frameworks that bridge the gap between abstract thinking and practical action.

I learned this firsthand while working with Sarah, a graduate student who came to me paralyzed by overthinking. She'd analyze every decision to death—which classes to take, which research direction to pursue, even which coffee shop to study in. "I can see all the possibilities," she told me, "but that's exactly the problem. I see too many, and I can't move forward."

During one of our sessions, I asked her to print out a simple visual framework I'd been developing—six lines of text that mapped common mental obstacles to what they actually destroy:

Fear kills dreams

Laziness kills ambition

Overthinking kills action

Doubt kills confidence

Stress kills progress

Ego kills growth

"Put this somewhere you'll see it daily," I suggested. "But here's the key—don't just read it. When you catch yourself overthinking, point to that third line and ask: 'What action am I avoiding right now?'"

Three weeks later, Sarah returned with a different energy. The simple visual cue had become her reset button. Instead of spiraling through endless analysis, she'd trained herself to recognize the pattern and pivot immediately to action. "It's not that I stopped thinking," she explained. "I learned to distinguish between thinking that moves me forward and thinking that keeps me stuck."

Sarah's breakthrough reveals a crucial insight: effective visualization works on two levels simultaneously—the images in your mind and the visual cues in your environment. When these coordinate strategically, they create powerful systems for change.

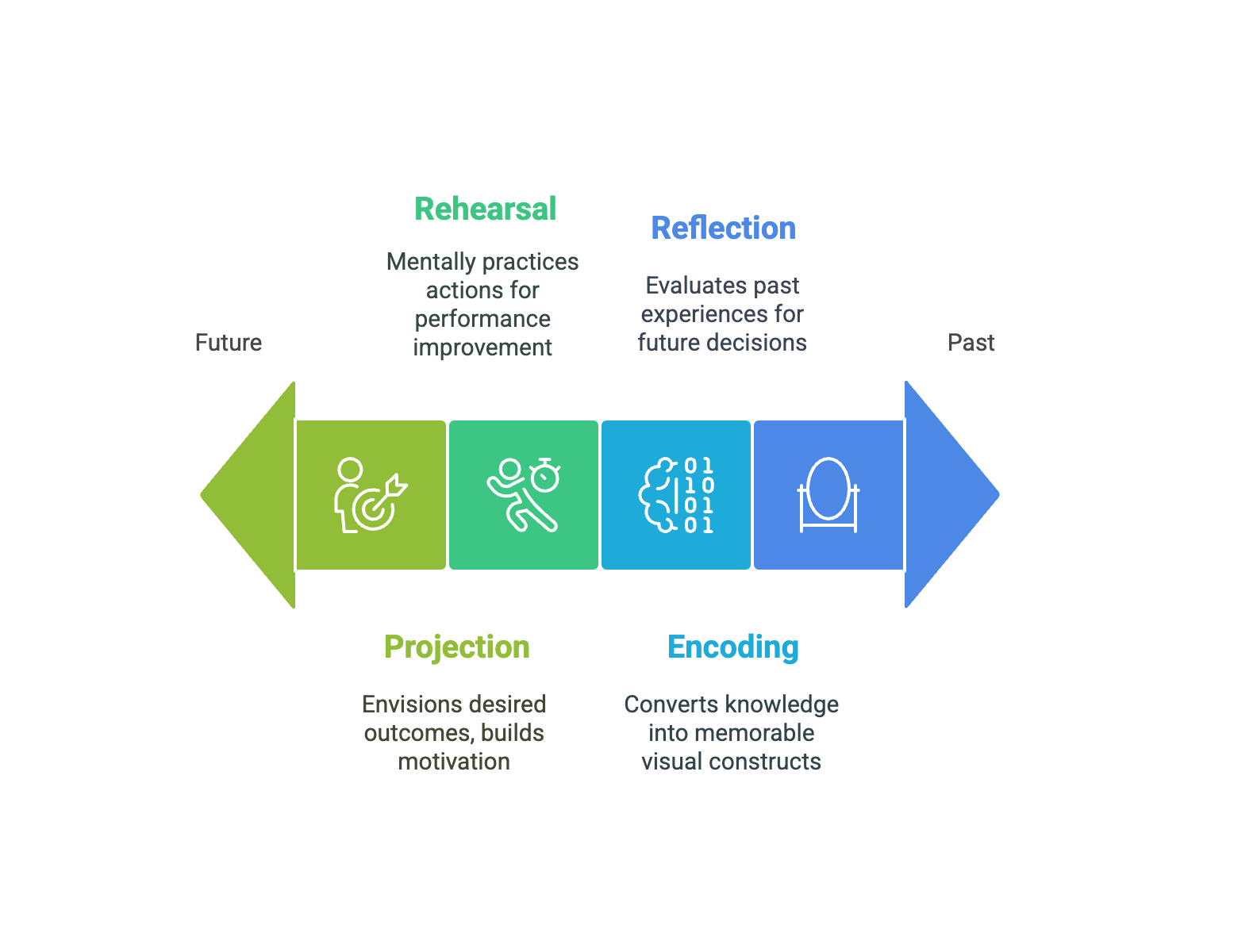

The Four Core Modes: Starting with How You Think

Before diving into complex frameworks, let's establish the foundation. Neuroscience research reveals that visualization isn't one general practice—it's actually four distinct mental activities, each activating different brain networks and serving different purposes:

Mode 1: Projection—Building Motivation and Vision

This is the "future-self" visualization most people know. You create compelling mental images of desired outcomes to maintain motivation and direction.

The science: Brain imaging studies show that visualizing future scenarios activates the same neural pathways as actual experiences, making goals feel more achievable and real.

When Sarah used this: After identifying that overthinking was blocking her action, she began visualizing herself as someone who thinks clearly then acts decisively—seeing herself confidently choosing a research direction and moving forward with purpose.

Your application: Spend 5 minutes each morning visualizing yourself successfully completing your most important goal. Include sensory details and emotions, not just the outcome.

If this isn't working: Your visualization might be too vague or unrealistic. Make it more specific and include potential challenges you'll overcome, not just perfect outcomes.

Mode 2: Rehearsal—Mental Practice for Performance

This involves mentally practicing specific actions or responses before real-world application—like athletes visualizing their performance.

The science: Research by sports psychologist Richard Suinn demonstrates that mental rehearsal creates muscle memory and neural pathways identical to physical practice, improving actual performance by up to 23%.

When Sarah used this: Before making any significant decision, she'd mentally rehearse the conversation or action, including potential obstacles and her responses. This replaced endless "what-if" analysis with purposeful preparation.

Your application: Before challenging situations (presentations, difficult conversations, complex tasks), spend 3 minutes mentally walking through the process, including how you'll handle potential setbacks.

If this isn't working: You might be rehearsing too generally. Focus on specific moments and responses rather than broad scenarios.

Mode 3: Encoding—Converting Knowledge Into Visual Memory

This transforms abstract concepts into memorable visual mental constructs, making complex information easier to learn and retain.

The science: Paivio's Dual Coding Theory proves that information processed both verbally and visually is recalled 65% more effectively than verbal information alone.

When Sarah used this: She created visual metaphors for her research concepts, turning theoretical frameworks into spatial relationships she could "see" and navigate mentally.

Your application: When learning new concepts, ask "What does this look like?" and create mental images, diagrams, or spatial relationships that represent the ideas.

If this isn't working: The concepts might be too abstract. Start by finding concrete analogies or real-world examples before creating visual representations.

Mode 4: Reflection—Processing Experience Through Imagery

This uses visualization to evaluate and understand past experiences, extracting insights for future decisions.

The science: Memory research shows that visualizing experiences from different perspectives enhances learning and pattern recognition, leading to better future decision-making.

When Sarah used this: At the end of each week, she'd visualize her decision-making moments like scenes in a movie, identifying patterns and celebrating progress in breaking her overthinking habit.

Your application: After important experiences (successes, setbacks, decisions), create a mental "highlight reel" to identify what worked, what didn't, and what you learned.

If this isn't working: You might be focusing only on negative experiences. Balance reflection between successes and challenges to build both learning and confidence.

The Visualization Matrix: Coordinating Mental and Environmental Practice

Once you understand the four modes, you can start using them strategically. This is where Sarah's printed framework comes in—it represents the power of coordinating what happens in your mind with what you see in your environment.

| Purpose | Mental (Internal) | Environmental (External) |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Projection mode—future-self visualization | Goal-aligned imagery, visual reminders like Sarah's framework |

| Focus | Rehearsal mode—single-task mental practice | Clean spaces, visual anchors that redirect attention |

| Learning | Encoding mode—concept visualization | Mind maps, infographics, concept diagrams |

| Decision-Making | Reflection mode—experience analysis | Decision trees, process maps, visual frameworks |

Sarah's breakthrough happened here: Her printed framework provided the external trigger, while she developed internal mental rehearsal patterns. Environmental psychology research confirms that visual cues in our environment influence behavior more powerfully than internal motivation alone.

Try this audit: Look at your current goals. Are you only visualizing mentally, or only relying on external reminders? Most people default to one approach and miss the synergistic effect of combining both.

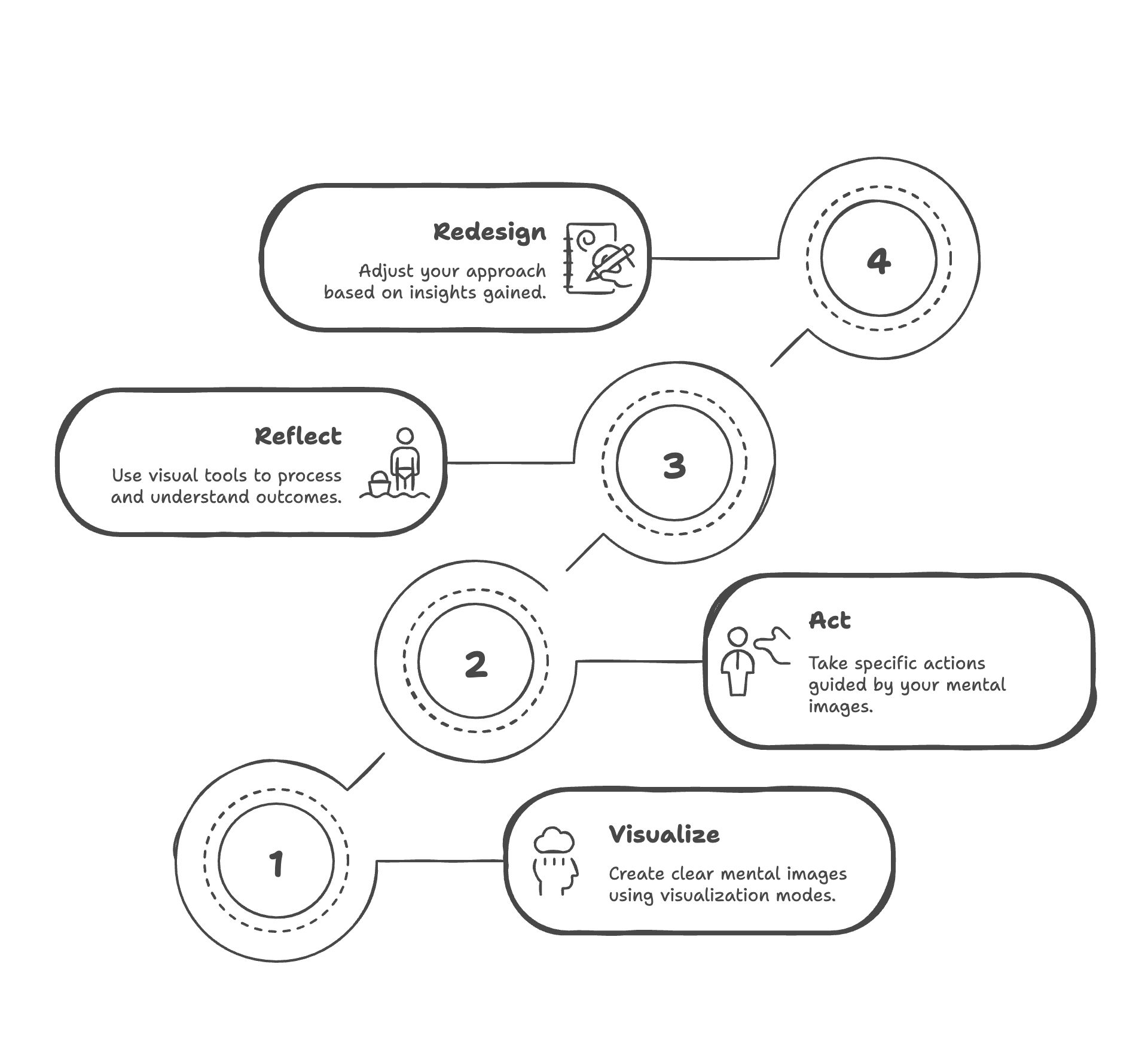

The Design Loop: Making Visualization an Ongoing Practice

Here's where the framework becomes truly powerful. Instead of treating visualization as sporadic inspiration, you turn it into a systematic practice based on iterative design principles:

1. Visualize → Use one of the four modes to create clear mental imagery

2. Act → Take specific actions guided by your visualization

3. Reflect → Use visual tools (mental or environmental) to process what happened

4. Redesign → Adjust your approach based on what you learned

Sarah's experience with the loop:

- Visualize: She'd use Projection mode to see herself making clear decisions

- Act: She'd set decision deadlines and stick to them

- Reflect: She'd review her printed framework, noting which mental obstacles came up

- Redesign: She'd adjust her environmental cues and mental rehearsal based on what worked

This loop transformed her relationship with decision-making from a source of anxiety into an evolving skill. Research on deliberate practice shows that this kind of systematic feedback leads to exponential improvement over time.

The key insight: Structure creates freedom. By providing a consistent process, you're free to experiment with content and let your approach evolve.

Environmental Design: The VIBE Framework

Not all visual aids actually help—some create distraction or cognitive overload. Sarah's framework worked because it met specific criteria based on environmental psychology research that you can apply to any visual element in your space.

The VIBE Assessment:

Before adding any visual tool, test it against these evidence-based criteria:

- Value: Does this clearly reflect what matters to you? (Sarah's framework directly addressed her core challenge)

- Interaction: Does it invite engagement rather than passive glancing? (Sarah had to actively point and ask herself questions)

- Balance: Does it add clarity or visual noise? (Six simple lines vs. cluttered motivational posters)

- Elaboration: Does it support deeper thinking? (Each line prompted self-reflection and pattern recognition)

Studies on cognitive load theory show that visual environments passing all four criteria enhance performance, while those failing any criterion can actually impair focus and decision-making.

Apply VIBE to your space: Walk through your workspace, study area, or home. Which visual elements pass the test? Which create distraction? What's missing that could support your goals?

Adapting the Framework: Start Where You Are

These tools work best when adapted to your unique situation. Think of them as thinking partners rather than rigid instructions—research on self-determination theory shows that autonomy in choosing methods increases both motivation and effectiveness.

If you're facing Sarah's challenge (overthinking):

- Start with environmental cues that interrupt analysis paralysis

- Develop Rehearsal mode practices for decision-making

- Use the Design Loop to build confidence through small wins

If you're struggling with motivation:

- Focus on Projection mode combined with meaningful visual reminders

- Design environmental cues that reconnect you with your goals

- Use Reflection mode to celebrate progress and adjust course

If you're learning complex material:

- Emphasize Encoding mode with visual concept mapping

- Create environmental tools like diagrams and frameworks

- Use the Design Loop to refine your learning approach

Getting started:

- Choose one mode that addresses your current most pressing challenge

- Create both a mental practice and an environmental cue

- Run the Design Loop for one week

- Notice what works and adapt the approach to fit your natural patterns

What If the Framework Isn't Working?

If you've tried multiple approaches and still struggle with visualization:

- You might be expecting immediate results. Visualization skills develop over time—research shows most people need 2-3 weeks of consistent practice to see significant changes.

- Your approach might not match your learning style. Some people are naturally better at mental imagery, others at environmental design. Start with your strength and gradually develop the other.

- The challenge might be deeper than technique. Sometimes difficulty with visualization indicates underlying stress, perfectionism, or executive function challenges that benefit from professional support.

Beyond Technique: Visualization as a Design Practice

The goal isn't to visualize more—it's to visualize more strategically. Whether you're facing a career transition, exploring your values, planning a creative project, or simply trying to make sense of where you are, these frameworks bridge the gap between abstract thinking and practical action.

Sarah's transformation wasn't about finding the perfect technique—it was about developing a systematic approach that she could adapt as her challenges evolved. Six months later, she applied the same principles to choosing her dissertation topic, building professional relationships, and even planning her post-graduation career.

The frameworks gave her something more valuable than solutions: they gave her a reliable process for turning uncertainty into clarity and mental imagery into real progress.

Start with whatever draws your eye. Print frameworks, sketch on them, adapt them freely. Use digital tools or grab pen and paper. Let the tools evolve alongside your thinking. The right questions can illuminate answers you already carry within you—these visual frameworks are designed to help you ask those questions and act on what you discover.

Research References

Core Visualization Research:

- Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual coding approach. Oxford University Press.

- Kosslyn, S. M. (1994). Image and brain: The resolution of the imagery debate. MIT Press.

Strategy-Specific Studies:

- Suinn, R. M. (1997). Mental practice in sport psychology: Where have we been, where do we go? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 4(3), 189-207.

- Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257-285.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.