Stop Planning, Start Experimenting: Your Guide to Career Design

Tired of overplanning your career? Discover how students are using small experiments—like energy audits and storytelling—to find meaningful paths. Stop guessing and start testing. Career design is less about answers and more about learning by doing.

Maya stared at her laptop screen at 2 AM, completely absorbed in designing a digital poster for a local nonprofit. She'd been working for three hours straight and hadn't noticed the time pass.

The next morning, she dragged herself through her economics seminar—the major she'd chosen because it seemed "practical"—fighting to keep her eyes open.

"Why do I feel more alive doing free design work than studying what's supposed to be my career?"

She asked me this during office hours, and that question launched an experiment that changed how I think about career development entirely.

For years, I've watched students (and let's be honest, myself included) wrestle with the big, messy question: What should I do with my life?

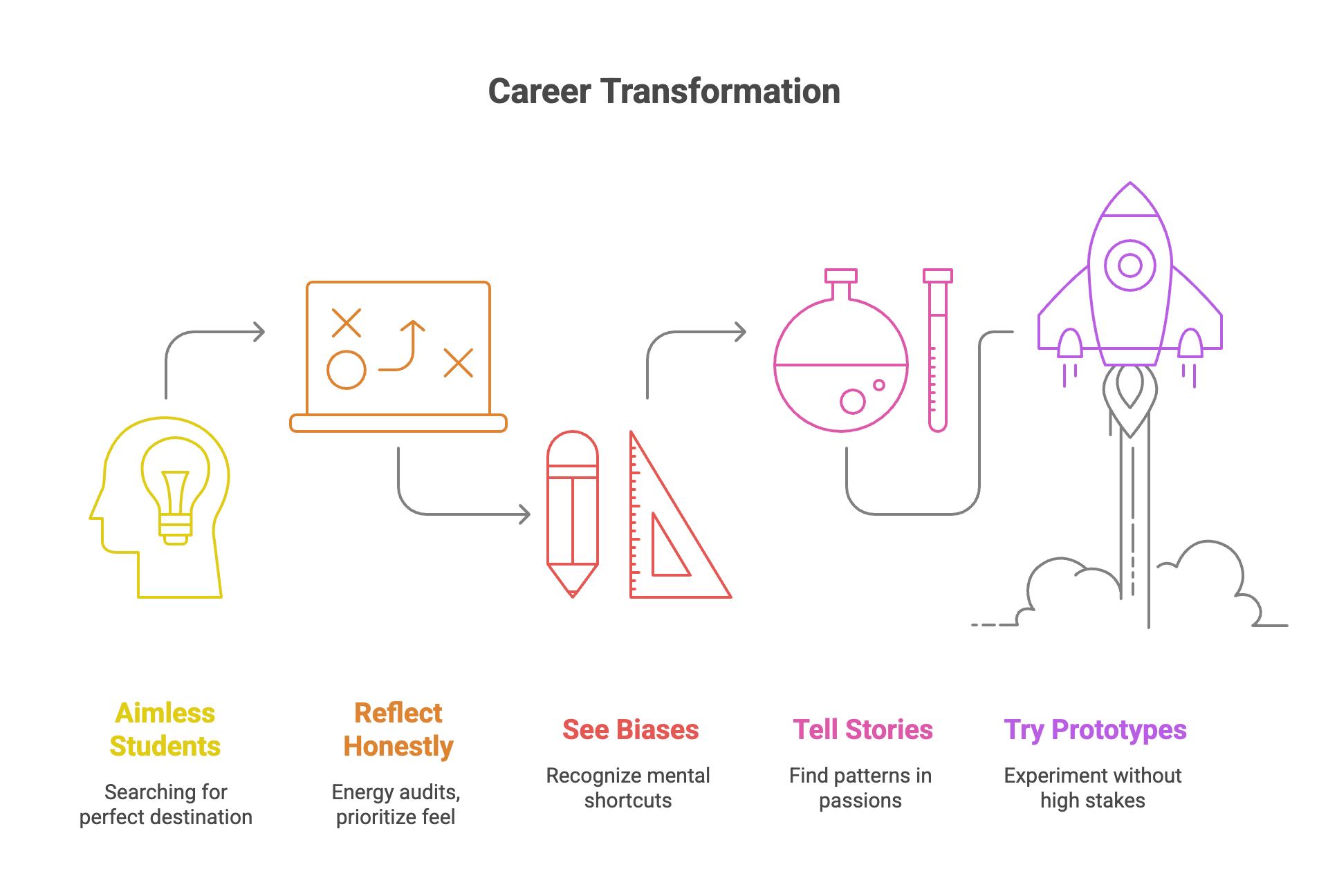

The traditional advice—make a plan, stick to it—rarely matches the reality of how fulfilling careers actually unfold. That's why I began experimenting with a different approach: treating career development like design thinking, with small tests instead of grand pronouncements.

These experiments didn't happen in a high-tech lab. They took place in casual workshops, hallway conversations, and late-night journaling sessions.

What follows are the four methods that consistently helped students find clarity, not through perfect planning, but through purposeful experimentation.

Energy Audit: Shifting Your Focus from 'Should' to 'Feel'

Back to Maya. Instead of telling her what she should want from her career, I asked her to pay attention to what actually energized her.

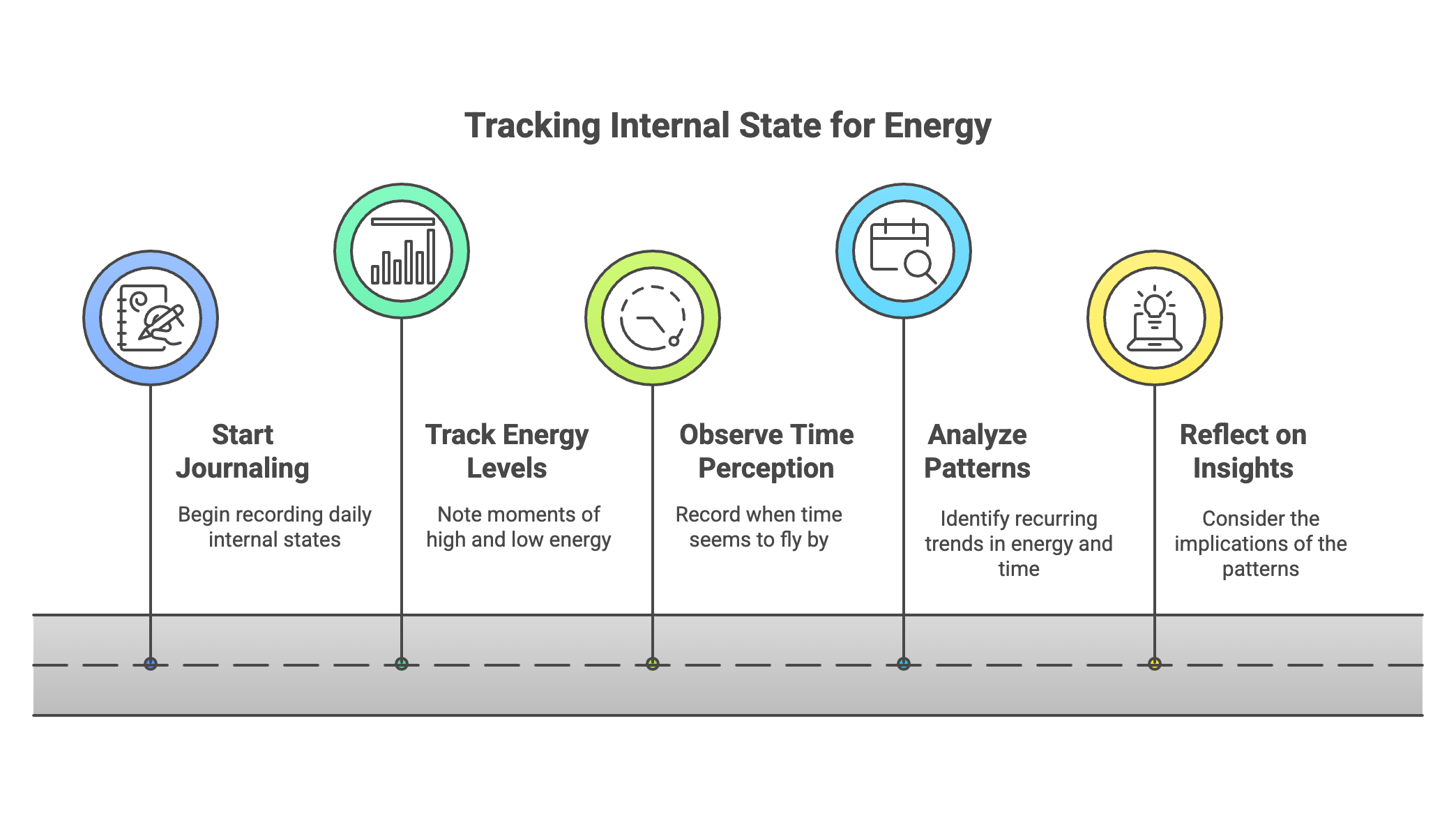

"Keep a simple journal for one week. Not tracking accomplishments—tracking your internal state. When do you feel energized? When do you hit a slump? When does time disappear?"

She looked skeptical but agreed to try.

Seven days later, she returned with pages of notes and a revelation:

"I never saw this pattern before."

Activities she thought should be productive—intensive research sessions, networking events, even some classes in her major—consistently drained her.

Meanwhile, her "side projects"—the digital art, volunteer design work, even organizing her friend's birthday party—left her feeling energized and engaged.

"I kept dismissing these as hobbies. But they're where I actually come alive."

Maya's energy audit became the foundation for exploring UX design and eventually landing an internship at a tech startup. But the real breakthrough wasn't the career pivot—it was learning to trust her own internal compass.

Try This Yourself:

For the next week, set three phone reminders throughout each day. When they go off, quickly note:

- What am I doing right now?

- How does my energy feel on a scale of 1-10?

After seven days, look for patterns. What activities consistently energize you? What drains you?

Your energy is data—use it.

Bias Blind Spots: The Case of the 'Dream Job' Illusion

Armed with better self-awareness, students still faced another challenge: the hidden forces shaping their choices.

Alex exemplified this perfectly. A junior economics major, he was laser-focused on landing a consulting role at a prestigious firm. When I asked why, his reasons sounded compelling:

"High pay, great exit opportunities, and honestly, everyone I know is trying for it."

But were these his reasons, or everyone else's?

The Experiment

We ran a simple test. I gave him three job descriptions with company names and salary ranges removed:

- One described a management consultant role

- Another nonprofit strategic planning position

- The third a market research analyst role at a creative agency

He read each carefully and ranked them by genuine interest. Surprisingly, the consulting role came in second.

"Interesting. Now let me show you which is which."

When he realized he'd ranked the nonprofit role highest—despite it paying 40% less than consulting—we had a moment of recognition.

"I think I've been anchoring on salary and prestige. And I've only heard the highlight reel from people who got consulting jobs. I never actually asked what the day-to-day work feels like."

The Insight

We spent the next hour identifying the specific biases at play:

- Anchoring bias (fixating on the first impressive salary he'd heard)

- Confirmation bias (only seeking information that supported his existing choice)

- Social proof (assuming what worked for others would work for him)

The goal wasn't to shame these mental shortcuts—we all use them—but to notice them when they were driving the bus so he could make more conscious choices.

Alex didn't abandon consulting entirely, but he did start exploring strategic roles at mission-driven organizations. Six months later, he landed a position he was genuinely excited about, not just one that looked good on paper.

Try This Yourself:

- Write down your current top career choice and why you want it

- Examine each reason: Is this based on my direct experience or assumption?

- What biases might be influencing me? (Anchoring, social proof, sunk cost, etc.)

- Imagine explaining this choice to someone who knows nothing about prestige or salary in your field—would your reasons still feel compelling?

Career Storytelling: Transforming Chaos into Coherence

Beyond audits and bias checks, how do we make sense of scattered interests and experiences? This is where storytelling unlocked something profound.

During a workshop, I asked students to write about the first time they felt genuinely proud of something they created—not for school, not for a grade, just something they cared about.

Lila wrote about baking a three-layer chocolate cake for her sister's birthday when she was twelve. But the way she described it caught my attention:

"I spent weeks planning it. I researched different frosting techniques, created a timeline for each component, coordinated with my mom about oven space, and even made backup plans in case something went wrong. When it came together perfectly and I saw my sister's face light up, I felt this quiet pride that I'd orchestrated something beautiful."

After she shared her story, I said:

"Lila, you just described project management."

Her eyes widened.

"I did?"

Suddenly, "project manager" wasn't just a job title from LinkedIn. It was a natural extension of something she'd been doing and loving since childhood.

Her story connected the dots between her love of event planning, her success coordinating group projects, and her satisfaction from seeing complex plans come together.

That's the magic of narrative. When we tell our stories—really tell them, with specifics and emotions—we often hear our potential paths for the first time.

Try This Yourself:

Think of three moments when you felt deeply proud of something you created or accomplished. Write 2-3 paragraphs about each, focusing on:

- What you actually did

- How it felt

Then read them as if they were about someone else. What patterns do you notice? What skills or inclinations show up repeatedly?

These stories often contain career clues hiding in plain sight.

Prototyping: "Why Small Actions Win over Big Decisions"

Even with better self-awareness and clearer stories, students still felt pressure to make perfect decisions. That's when we introduced the most powerful concept: prototyping.

Jamie, a psychology major, had developed an interest in public health but felt paralyzed by the implications:

"If I pursue this, I'd need to completely change my academic focus, maybe go to grad school, basically restart everything."

"What if you didn't? What if you just prototyped your interest?"

Instead of switching majors or applying to programs, Jamie committed to volunteering four hours a week at a community health clinic. Low stakes, high learning.

The Results

Three weeks in, he reported back with nuanced insights:

"It's not exactly what I imagined. There's way more administrative work than I expected—tracking patient visits, organizing health education materials, coordinating with different departments. But here's the thing: I actually enjoy the administrative side. I like creating systems that help things run smoothly."

This small experiment didn't redirect his entire academic career. Instead, it refined his understanding of what public health work actually involved and revealed an unexpected strength in health program coordination.

Six months later, Jamie designed an independent study combining psychology and public health administration. He'd found his niche not through a dramatic pivot, but through a series of small, informed steps.

Try This Yourself:

Pick one career interest that feels too big or risky to pursue fully. How could you prototype it this month?

Could you:

- Volunteer for 3 hours?

- Shadow someone for an afternoon?

- Take on a relevant project at work?

Start with the smallest possible experiment that would give you real information.

The Unexpected Path: What I'm Learning (and You Can Too)

Here's what emerged from hundreds of these small experiments:

You don't need a perfect plan. You need better ways to try.

When students created space to:

✓ Reflect with honesty (energy audits that prioritize feel over should)

✓ See their biases without shame (recognizing mental shortcuts without judgment)

✓ Tell their stories with pride (finding patterns in what they've always loved)

✓ Try things without high stakes (prototyping instead of pivoting)

...the entire career conversation shifted.

It became less about arriving at the right destination and more about evolving through conscious experimentation. Less daunting quest, more insightful journey.

The students who embraced this approach didn't just find jobs—they found work that felt like a natural extension of who they already were.

Your Next Experiment

Ready to ditch the "perfect plan" and start experimenting? Here's how to begin this week:

Energy Audit (5 minutes to start)

Set three daily phone reminders. When they go off, note what you're doing and rate your energy 1-10. Do this for just three days to see initial patterns.

Bias Check (10 minutes)

Write down your current top career goal and list three reasons why you want it. For each reason, ask: "Is this based on my direct experience or assumptions?"

Story Mining (15 minutes)

Write about one time you felt proud of something you created. Focus on what you actually did and how it felt. Read it back and notice what skills or preferences emerge.

Micro-Prototype (1 hour this week)

Pick one career interest and find the smallest way to try it. Send an informational interview request, volunteer for two hours, or take on a related project.

The goal isn't to solve your career puzzle in a week. It's to start treating career development like the iterative, experimental process it actually is.

💡 Want to try this yourself? Scroll down to the interactive toolkit at the end of this article to complete your own 7-day energy audit with guided tracking tools.

🧪 Stop Planning, Start Experimenting

Your Interactive Career Design Toolkit

Method 1: Energy Audit

Shifting Your Focus from 'Should' to 'Feel'

Set 3 phone reminders throughout each day. When they go off, quickly note what you're doing and rate your energy level. Your energy is data—use it.

Continue this pattern for 7 days. Use your phone to set 3 daily reminders at different times.

Method 2: Bias Blind Spots

Seeing the Hidden Forces Shaping Your Choices

For each reason you listed above, consider these common biases:

Imagine explaining your career choice to someone who knows nothing about prestige or salaries in your field. Focus only on the actual work activities.

Method 3: Career Storytelling

Transforming Chaos into Coherence

Now read your three stories as if they were about someone else. What patterns do you notice?

Method 4: Prototyping

Why Small Actions Win Over Big Decisions

How could you prototype this interest this month with minimal commitment but maximum learning?

Choose the smallest experiment that would give you real information:

When will you start and complete this experiment?

Based on your insights, what's the ONE thing you'll try this week?

Ready for personalized feedback on your career experiments?

📋 Copy Results: Copies your responses to clipboard

💾 Download: Saves as PDF for your records

Send to: seth.looper@gmail.com

I personally review every submission and send tailored feedback within 48 hours.

💬 Prefer a Simple Message?

Just tell me your biggest insight and what you plan to try:

🌟 Share Your Experiment

Help others discover the power of career experimentation: